|

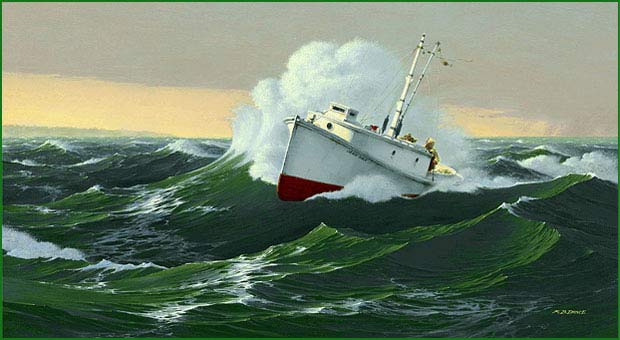

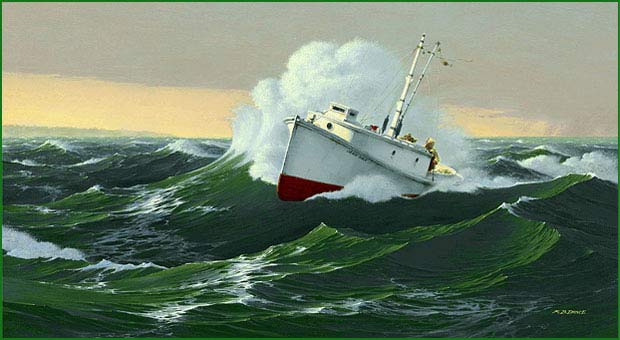

| Despite

her graceful lines, the Jean Dale was constructed

strictly as a working boat in the 1940s. Handcrafted

of longleaf pine and juniper planks, the sink netter

was built to handle the rigors of year-round commercial

fishing as evidenced by these photos of the boat in

the late 1960s on Harker's Island. |

The

Jean Dale

What

do you know about the Jean Dale?" I yell above the

sounds of circular saws and hammer beats. The September

sun is retreating westward toward Beaufort, and the salt-laden

air of Core Sound is thick all around. Clarence Willis drives

one last nail into a juniper plank and motions for his helpers

to knock off for the evening. Tanned island men silently

pack up their tools amid the sawdust and lumber and disappear

in the fleeting light, leaving me alone with Willis and

his son, Junior.

"What you want to know about her?" Willis asks

back sheepishly, arms folded, with an old hammer in the

crook of one arm and his strong back leaning squarely against

the bow of the unfinished wooden skiff. He looks me over

with the distrust of a stranger bearing beads for a one-sided

trade. I understand his distrust. Here on Harkers Island,

I'm considered a "dingbatter," an outsider. And

it's folks like me-in Willis' and most other natives' views-who've

changed this island, its people and their way of life.

"She is a Core Sound sink netter, right? One of the

last of her kind left?" I know enough to ask the right

questions.

"She was just another fishing boat-the Jean Dale. There

was a time when there were 50 or 60 boats like her on this

island," Willis responds matter-of-factly. "But

there ain't many left anymore." His 71-year-old blue

eyes flash back to the past, and I know he knows more. His

leathered arms unfold and relax as he continues. "She was just another fishing boat-the Jean Dale. There

was a time when there were 50 or 60 boats like her on this

island," Willis responds matter-of-factly. "But

there ain't many left anymore." His 71-year-old blue

eyes flash back to the past, and I know he knows more. His

leathered arms unfold and relax as he continues.

"She

was a good sea boat built for Harry Lewis back in the early

'40s" Willis explains as he lays down the hammer on

a sawhorse. "She was a real fishing boat, maybe 40

foot long. Harry worked her year-round-shrimping and pulling

nets," he said. "Sank twice and caught afire once,

but they didn't give up on her."

And

the Jean Dale didn't give up either. The planked boat, built

of heart pine and juniper, was fished nearly continuously

for 50 years, Willis explained, bringing back loads of shrimp,

gray trout, spot and sea mullet to Harkers Island. Once,

Harry sank her off Brown's Island in rough seas with a heavy

load of jumbo croakers -maybe 120 to 125 boxes full. "It

brigged up on him; and with so much weight, the stem went

down. But they raised her and got her dry in a day or two

and went back at it again."

Harry

Lewis was the sole owner of the Jean Dale. And when he got

too old to fish her, his grandson took up fishing the boat

for a while. "She didn't owe Harry nothing," Willis

said. "She had well paid for herself."

"Who

built the Jean Dale?" I blurt out, guessing that Willis

knows much more.

"Brady

Lewis built her, along with some other men on the island.

And I helped work on the Jean Dale when I was young,"

he explains. "Brady Lewis-well, he's the one that started

this (boat-building) mess with the flared bow-'flow'r' we

call it, and he taught me too. I quit school when I was

13 and started working for Brady. At first, he would just

let me hold the planks. But he got to where he would trust

me more to cut the planks."

Famed

boat-builder Brady Lewis crafted the Jean Dale, with the

help of others including Clarence Willis (above) who was

a teen-ager at the time. Now in his 70s, Willis is working

with others on Harker's Island to restore the historic fishing

boat.

|

|

| Famed

boat-builder Brady Lewis crafted the Jean Dale,

with the help of others including Clarence Willis (above)

who was a teen-ager at the time. Now in his 70s, Willis

is working with others on Harker's Island to restore

the historic fishing boat. |

The

Jean Dale was indicative of the "Harkers Island boat,"

Willis explained. She was narrow, long and graceful with

a distinctive flared bow-made famous by Brady Lewis-and

a low transom and a rounded stern to prevent the fishing

nets from hanging up when they were pulled in by hand by

a three-man crew. She had a fairly flat bottom for a shallow

draft to navigate the waters of Core Sound. But the flared

bow, with just enough dead rise, helped cut the waves offshore

in heavy seas. "The narrower the boat, the more dead

rise," Willis said. "A narrow boat was a better

sea boat. But you didn't let her get side-to in rough seas.

You took your waves head-on. And the round stern worked

good for pulling in the sink nets," he added.

The

Jean Dale was fitted with a six-cylinder Chrysler gasoline

automobile engine and had a 22-inch wheel (propeller), Willis

explained. But she could make 18 to 20 knots in good conditions

at 3,400 rpm's. And she had a distinctive "doghouse"

up front where the captain could pilot her in rough conditions.

Brady

Lewis-considered by many the father of North Carolina boat

building-is credited on Harkers Island with developing the

flared-bow boat. He devised a simple mathematical formula

to lay up the narrow juniper planks in various widths in

nearly seamless perfection to create the distinctive bow

shape. "He just got it in his head, the flow'r,"

Willis said. "Besides, it makes a prettier boat anyhow."

Before the days of modern fiberglass, Brady Lewis taught

Willis and many others on the island how to work out the

calculations for the graceful curves of wood. In his nearly

60 years as a boat-builder, Willis has built hundreds of

wooden boats, from skiffs all the way up to 70-footers.

But he's never touched fiberglass and never will. "Can't

stand the stuff. In my opinion, it makes a sorry boat-too

easy to bust her with fiberglass. Wood is much stronger.

I wouldn't even try to guess at the number of wood boats

I've built. I've retired twice from it, but then somebody

on the island wants me to build 'em a boat."

That's

where this 24-footer he's working on came from. The plans

themselves are not written down-each one comes from Willis'

head, just like his teacher, Brady Lewis, did it. But too

few builders work with wood anymore.

Willis

wistfully thinks back. "I wish it was back like it

was 20 years ago. There's too few working in the fishing

now, and wood and materials are too expensive. There's still

some juniper left, but no heart pine. And everybody wants

fiberglass now. Used to be people made boats for people

who used boats to work and earn a livin'. Then the big people-the

moneymen-got into it with fiberglass. Naturally, the dingbatters

came in too. They put the damper on us and wooden boat-building."

History

of the Core Sounder

Built

as a commercial workboat, the clean lines of the Jean Dale,

with its flared bow and rounded stern, represent a pinnacle

in North Carolina boat building, explains Mike Alford, former

curator of maritime history at the North Carolina Maritime

Museum. And the lasting popularity of the flared bow made

famous by the wooden boat-builders on Harkers Island and

Core Sound has spread up and down the East Coast and is

still found in an exaggerated form in the modern fiberglass

fishing boats of today.

The

Core Sounders, as this class of boat was called, once dotted

the small harbors of Harkers Island and nearby coastal communities.

Sleek and gleaming white, they had a low, graceful sheer

that swept up to a smart, flared bow, while the aft end

terminated in a low, almost dainty round stern, Alford explained.

There was a simple low cabin forward that sheltered a galley,

a couple of berths for the crew and a bad-weather steering

station. Directly over the station a hatchlike windowed

box allowed the helmsman to poke his head up and look around.

Built on the island, and in a few nearby mainland communities,

they ranged in length from around 35 feet to more than 40

and were powered by single engines.

"In

the building of boats, there is a general maxim that changes

occur slowly and only when necessary," Alford said.

"Probably nothing ever overhauled the boat builder's

status quo more significantly, or as rapidly, as did the

advent of the internal combustion engine."

The

story of the Core Sounder began when the fishing community

began to accept gasoline engine power as a viable alternative

to sail. In North Carolina that was near the end of the

first decade in the 20th century. Three decades later, the

Core Sounder emerged. Although elements of its design and

construction can be traced back to sailing craft, the Core

Sounder represents what might be considered the perfection

of a power-driven hull, explains Alford, not as the end

result of a series of modifications to sailing hulls. The

story of the Core Sounder began when the fishing community

began to accept gasoline engine power as a viable alternative

to sail. In North Carolina that was near the end of the

first decade in the 20th century. Three decades later, the

Core Sounder emerged. Although elements of its design and

construction can be traced back to sailing craft, the Core

Sounder represents what might be considered the perfection

of a power-driven hull, explains Alford, not as the end

result of a series of modifications to sailing hulls.

Boat-building

has always been a major interest in North Carolina since

its earliest days as a colony. Prior to the Civil War, boats

built with logs were the rule. Following the war, two boat

types dominated inshore fish-ery and commercial activities

in the state. The round-bottom shad boat, with its versatile

sprit-main and jib rig, prevailed in the northern sounds-the

Albemarle, Pamlico and Croatan. Core Sound, to the south,

was the stronghold of the sharpie-a flat-bottomed immigrant

from Connecticut. By the late 1800s, sharpies were found

as far south as Wilmington and Southport, and as far north

as the sounds extended. But Core Sound was their stronghold.

By

the early 1930s, with powered boats everywhere, the new

challenge was a demand for "bigger and better"

boats that could navigate the shoal sounds, contend with

summer squalls and venture into deep-sea fishing grounds.

Enter the Core Sounders.

Brady

Lewis and those who learned from him began producing the

first of the Core Sounders in the 1930s. Earlier versions

were typically built on a 4-to-1 ratio of length-to-beam,

and were powered by engines of 115 horsepower or less. Just

before World War II and immediately after, boats experienced

a trend that saw horsepower double in a short time, and

length-to-beam ratios began a downward trend toward 3-to-1.

The

Jean Dale represents the best of the postwar boats, Alford

said. She is simple and clean, and has all the features

in the appropriate proportions that give the Core Sounders

their distinctive look: low freeboard, saucy bow flare and

a graceful round stern. By the early '50s, the use of larger

and faster engines resulted in less graceful proportions.

Deeper and more robust, the round stern was no longer the

sweetly balanced end of a sleek, easily driven hull. At

the same time the flared bow sections grew more and more

extreme. But the Jean Dale had the grace and charm that

well-balanced elements of design give to a boat. |